From ‘Sunrise On The Reaping’ to ‘Of Mice And Men’ to ‘Get A Life, Chloe Brown’, Reading Is A Political Act

When prospective readers are young and first introduced to fairytales, they are often provided with books with clear moral messages at the end: ‘Alice In Wonderland’ (1865) by Lewis Caroll encourages curiosity and to embrace the turbulence and unpredictability of life, Dr. Seuss’ ‘The Lorax’ (1971) criticises industrialism and consumerism and encourages a love and respect for nature and the environment and the story of ‘Elmer the Elephant’, (1990) by David McKee encourages you to embrace what makes you different and to appreciate these qualities in others.

While older children and adult readers do not need to be spoon-fed the morals of their books in the same manner, some books have clearer moral messages and or insights into the world. This, however, doesn’t mean that books aren’t political or able to spread important messages through characters or the events of their stories. I personally feel like Suzanne Collins doesn’t pull punches when it comes to the gravitas of her characters’ experiences.

‘Sunrise On The Reaping’ by Suzanne Collins was released on March 18th 2025. It is Collins’ second prequel to her ‘Hunger Games’ trilogy, and follows the story of Haymitch Abernathy in the 50th Hunger Games.

Like all of Collins’ books, ‘Sunrise On The Reaping’ is politically charged, and likely will result in being banned due to the rebelious nature of Haymitch’s character, and Collins’ stressing that the way images and accounts are distorted to evoke a particular message, only adds fuel to the fire. But the political nature of reading goes far beyond dystopia.

In the lead-up to the 2024 Presidential Election, I happened across content that showed the scope of current and further prospective book bans in the States with reference to Trump’s campaign. Among which, content creators highlighted the fact that Collins’ trilogy has been banned consistently.

‘The Hunger Games’ was reported as The American Library Association (ALA)’s twelfth most banned and or challenged books between 2010 and 2019. Another title that made its way onto that list was ‘The Hate U Give’ by Angie Thomas, which was ranked at the thirtieth most banned or challenged book.

‘The Hate U Give’ by Angie Thomas was released in 2017. As a critique on police brutality, Thomas was critical of the notion of why her book was banned. It is often criticised for containing the f-word.

Thomas has responded to criticism about her books and their subsequent banning on multiple ocasions. In 2018, at the Cleveland Public Library, Thomas addressed the notion of ‘The Hate U Give’ being banned due to the use of the f-word, where in which she said:

‘There are 89 f-words in ‘The Hate U Give;’ I know because I counted them, and last year, more than 900 people were killed by police. People should care more about that number than the number of f-words.”

Since 2018, Thomas has been vocal in defence of her books, because she does not write with the intent of the books being banned. Instead, as above, Thomas has indicated that there is likely a reason why ‘The Hate U Give’ was banned. With reference to her later releases, Thomas has expressed on her X (formerly Twitter) account back in 2022, that:

“It’s emotionally taxing to have my book(s) banned. But not because they’re my books, but because all I can think about is the message it sends to the Black kids who see themselves in my books. They deserve to have their stories told whether it makes you comfortable or not.” – 7th Jan 2022 via X

When referring back to the ALA’s list, one can find ‘Of Mice and Men’, the classic novella by John Steinbeck, ranked at number twenty-eight.

When I was in secondary school, we read ‘Of Mice And Men’, released in 1937. Its a novella that explored the nature of the Great Depression and how the wealthy exploited the poor, and the suffocating nature of the American Dream. It has been banned in the States for multiple reasons in the past, including but not limited to Steinbeck’s depiction of women, and the use of racist and abelist language.

Considering that, specifically through the lens of Steinbeck’s novel, there is a lot to unpick about the notion that reading isn’t a politically charged act.

‘Of Mice And Men’ is a poignant novel that tells the story of George and Lenny, two men who travel to California and take up work at a ranch. In this book, they share a bunkhouse with several other malnourished, ambitious people with dreams beyond the ranch, including Curley’s Wife, a woman without a given name, that is treated as an object of desire, and solely her husband’s property. She dreams of being a Hollywood starlet, wearing red lipstick and styling her hair into little sausage-like curls.

This book confronts themes of racism through the character of Crooks, who doesn’t live among his colleagues as the only black man at the ranch. His back is twisted, marred through abuse when he was a slave, and while the illusion of his freedom is provided, he lives in isolation, segregated from his peers, and housed beside a pile of manure.

‘Of Mice and Men’ confronts the cruel nature of the American Dream during the Great Depression, where in which people dreamed of self-sufficiency and prosperity without the fear of debt, or starvation. Yet despite this dream being thrust down the throats of these characters, they are knocked back at every corner, being paid meager sums for their back-breaking work. Candy, an older man at the ranch lost an arm while working with farm equipment, and yet, the use of the machine is considered unabashedly normal and Steinbeck does not actively acknowledge the other characters being afraid of using the equipment.

It is criticised for the treatment of Curley’s Wife and Crooks, including the use of the n-word, which is often self-censored when reading aloud or removed from the books by publishers. It has a clear socio-political message and is a raw and evocative story that criticises the idea of one of the foundations of American society.

But, there is more to the political nature of books than just the upfront criticism of the world around an author when they write. Dystopian novels make this message exceptionally clear.

This relationship between literature and the messages it conveys to its readers goes beyond genres where characters overthrow a corrupt system like you may find in dystopias, science fiction and fantasy novels.

Consider the romance genre; romance novels are a deep and evocative exploration of not only characters’ relationships with their partners, but often with themselves. With hundreds of individual tropes, not only can readers explore a vast number of prospective scenarios, but they can live out their own romantic fantasies that may be glaringly similar to their own circumstances. Escapism in literature isn’t uncommon, just as seeking the validation that you are not alone.

Single-parent romances are a great example of this from the get-go, because they provide readers the opportunity, as potential single parents themselves, to know that the world of romance isn’t closed off to them. There are people in the world, whether you be queer, like Claire in ‘Delilah Green Doesn’t Care’ (2022) by Ashley Herring-Blake, or straight.

Another great example of this all-encompassing, everyone deserves love message is romance novels that showcase protagonists with disabilities. A great example of which happens to be Chloe in Talia Hibbert’s 2019 novel, ‘Get A Life, Chloe Brown’.

‘Get A Life, Chloe Brown’ is the first of Hibbert’s romance novels following the Brown sisters Chloe, Dani, and Eve.

Chloe and her love interest, Redford Morgan, also known as Red, have a nuanced love story, but what is likely more empowering is the fact that Chloe Brown is a plus-sized, disabled woman who is shown to be loved by her family and friends, considered accomplished and talented. She is worthy and deserving of love. This is a theme stressed in the rest of Hibbert’s series as well as romance novels as a genre.

The character of Chloe Brown is a great figure that readers can relate to, and project onto. She is a complex but inherently likeable character. Her relationship with herself; from her body, her appearance and her disability fluctuates as it does with anyone. But, what isn’t unwavering is the value she has to those around her. And, surely, nothing is more empowering in a world which is actively trying to silence women than a woman who knows she is worthy and deserving of love.

Romance novels, which showcase the power a woman has to make choices about herself, her boundaries and her body echo this sentiment and passively provide women with these perceived high expectations when it comes to men. While this could refer to the idea of a boyfriend or husband sweeping a woman off her feet on a dragon, it is more likely to be a man that respects his partner’s boundaries, wishes and wants.

For example, in Olivia Dade’s ‘At First Spite’ (2024), the female lead, Athena, purchases the house next door to her ex-fiance’s brother, and as she attempts to acclimate to her new home and environment, Athena’s mental health takes a toll.

Having not seen Athena in days, an uncharacteristic change in her behaviour, her love interest Matthew seeks her out, and goes next-door to investigate.

Her house is a mess, and she hasn’t taken care of herself, mental health having taken a nose-dive. He admits her hair is greasy and unwashed and she smells like she hasn’t bathed in a few days. Instead of being critical of her, and using her vulnerable state to pour metaphorical gasoline on their rivalry, he offers kindness, but also the option for her to simply send her away. He is attentive, and genuine and helps her when her mental health dips. This showed a glaringly important message to Dade’s readers: even when Athena was depressed and isolated from friends, rivals, and colleagues, she deserved kindness and care, and Matthew offered it without hesitation.

Women’s rights, particularly their reproductive rights are being taken away in the USA. Having romance novels, which statistically have a higher female readership, echoing the sentiment that women should be able to speak for themselves, make their decisions and choose what they want to do, whether that be by favouring casual sex instead of committing to a relationship, and calling out people who criticise her for it as Anastasia or Stassie did in Hannah Grace’s ‘Icebreaker’ (2022) or calling out their partner on inappropriate and unacceptable behaviour like Sadie does in ‘In Your Dreams, Holden Rhodes’ (2022) by Stephanie Archer or demand access for herself like Frankie does in Evie Mitchell’s ‘Knot My Type’ (2021), there is one common theme, these women deserve love, and they are speaking up against things that affect them personally. Just like Starr did in ‘The Hate U Give’ and Katniss did in ‘The Hunger Games’ trilogy.

Speaking of ‘The Hunger Games’ trilogy, there is a lot to say about the dystopian genre. Dystopian novels conjure up scenarios that focus on controlling government powers oppressing a group of people that are considered lesser, and oftentimes, this organisation echoes systemic oppression that real people in minority groups experience, but through the lens of fiction. The genre encourages calling out organisations and people that are causing harm to others, rising up and rebelling against systems that try to force you to exist within certain parameters.

While aspects of these regimes are exaggerated for added shock, nobody is sending children into an arena to fight to the death at the moment, the politics behind these jaw-dropping examples are well rooted in these lived experiences. A great example of this is the ‘Delirium’ series by Lauren Oliver (2011-2013). The pitch for this series is the idea that love is considered a disease.

In this series, readers follow the protagonist, Lena as she goes from looking forward to being administered the Cure to falling in love, to meeting Alex, a boy from the Wilds, who doesn’t see love through this same lens, and changing Lena’s worldview.

Does this perhaps seem familiar? Perhaps, because the idea of love being a disease can be traced back to the queer community. At the time of the book’s publication, same-sex marriage was still illegal in both the USA and the UK.

It is also worth remembering that until 1967, same-sex relations, in public and private were considered illegal in the UK, and Section 28 impacted queer education in the UK from 1988 until 2003. Similarly, in the States, the process of decriminalising same-sex relationships extended from 1962 (starting with Illinois) to 2004 (National Decriminalisation). There were also, as of 2023, 64 countries where in which it was still illegal to be gay.

Without even touching on the AIDS crisis, which was considered a gay disease, even though it could be contracted by both queer and heterosexual people, the image of queerness being a disease and love being a disease seems clear, whether Oliver intended it or otherwise. Yet, Lauren Oliver’s dystopia dubs love as a disease for all, and this Cure (which, in hindsight, I likened to the idea of gay men being experimented upon and castrated during the Holocaust) is considered the norm for the greater good, and yet Lena wants to love Alex. Their budding love was a rebellion of its own right, without even reflecting on the events of the rest of the series.

Did you know that seven of the top ten most challenged books, recorded by ALA in 2023 were flagged for including LGBTQ+ content or themes?

Similarly, did you know that during conquest and dictatorships, where certain rhetoric was being encouraged, books were burned to remove the content they contained from the world, so in response to censorship and significant abortion bans, Margaret Atwood, author of ‘The Handmaid’s Tale’ (1985) released an ‘unburnable edition’ in 2022 which was described by Penguin Random House in The Guardian as “ special edition of a book that’s been challenged and banned for decades. Printed and bound using fireproof materials, this edition of Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale was made to be completely un-burnable. It is designed to protect this vital story and stand as a powerful symbol against censorship.” because ““Across the United States and around the world, books are being challenged, banned and even burned.”

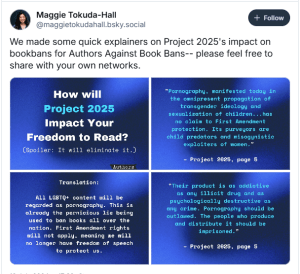

Did you know that records are being deleted in the USA, which include references to diversity, such as the word “gay”. This aligns with Project 2025, a right-wing wishlist for Trump’s second term. This same document expressed a desire for educators and public librarians who provide access to [“pornographic” and “obscene” books which includes the “omnipresent propagation of transgender ideology” which can be implied to be queer media, such Alice Oseman’s ‘Heartstopper’ (2019 – Present) which features a proud, young, trans girl called Elle)] should be “classed as registered sex offenders? This interpretation has been echoed by a co-founder of Authors Against Book Bans, Maggie Tokuda-Hall.

Tokuda-Hall expressed her interpretation of the below quote from Project 2025, on Bluesky in 2024, “Pornography, manifested today in the omnipresent propagation of transgender ideology and sexualisation of children … has no claim of First Amendment protection. Its purveyors are child predators and misogynistic exploitation of women” essentially means “all LGBTQ+ content will be regarded as pornography. This is already a pernicious lie being used to ban books all over the nation. First Amendment rights will not apply, meaning we will no longer have freedom of speech to protect us”. And while Trump denounced the document during his campaign, he did hire some of its authors.

Whether a book is declaring its moral from the rafters, encouraging people to speak up for what’s right and call out systems that cause people harm, or a love story that encourages readers that they are worthy and deserving of love, regardless of their past and history, there is always something deeper in literature.

Reading is always political. There is always a message, whether active or passive, being passed through the story for the reader to engage with. Dystopia or not.