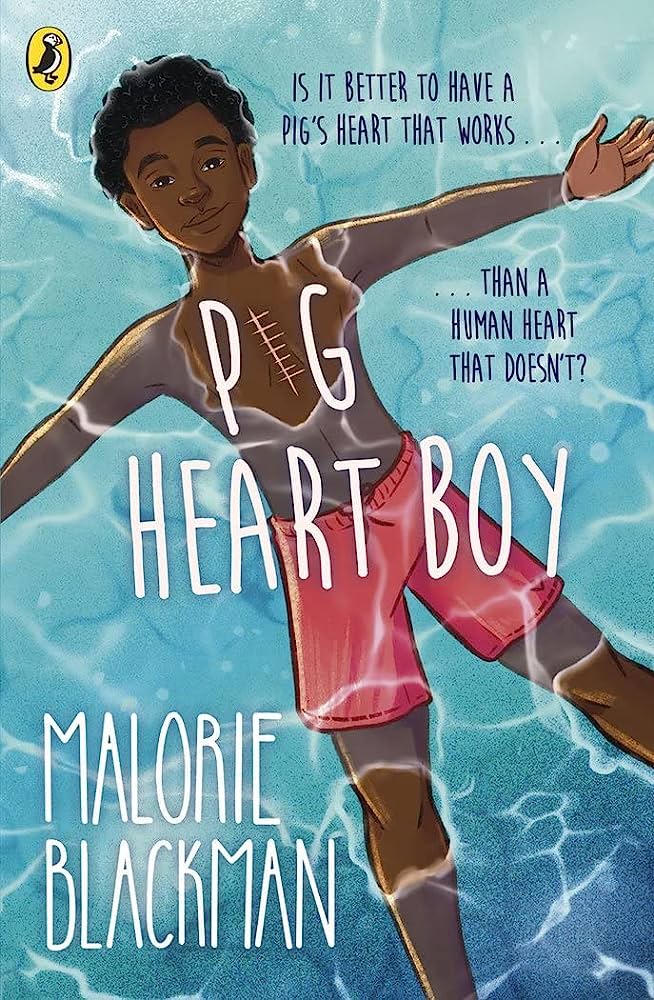

Book Review: Pig Heart Boy by Malorie Blackman

‘Pig Heart Boy’ by Malorie Blackman was published in 1997. It was her twenty-second novel. The story followed thirteen-year-old Cameron, who, after contracting a viral infection when he was eleven, found himself with a heart condition, and his quality of life was deteriorating, and quickly. So when his father takes a risk and reaches out to a doctor, experimenting in genetic modification and organ transplants, Cameron is given the chance of a lifetime: an opportunity to get a heart transplant from a pig. Not a human donor.

Cameron is desperate. He has felt his strength decreasing, and acknowledges how hard this is on his family. He’s been high on the list for donor hearts, but to get one, a donor had to die. When a human donor had come about in the past, the organ had been rerouted for a different patient who was at even greater risk, all while Cameron was on his way to have that lifesaving surgery. Heart disease isn’t something you’d wish upon anyone, especially not a chid. Cameron wants to live. And without this experimental surgery, he won’t survive much longer.

The story delved into many themes that were incredibly hard-hitting and evocative, even after twenty seven years! Whether that be the right to privacy, the ethics of experimenting on animals and who has the right to life.

It still offers a harsh, ethical debate on whether humans should use the advancements of science to their benefit, even if it means killing animals. If the death of a pig, for its heart for a transplant to save a human life, and the rest was waste, it would be a sad product of the medical industry, however, there is no indicator as to what happened with the rest of the pig, whether she was sent to a butcher so her meat could feed families is unforeseen, but you don’t see activists slandering every independent butcher or restaurant that isn’t vegetarian or vegan. It was hypocritical.

I loved the reference to ‘Jurassic Park’ in this book. It’s clear, even in 1997 that the idea that genetic power could become a behemouth or a catastrophe just waiting to happen, long before the franchise repirsal in ‘Jurassic World’, where gene-splicing to make hybrid species for consumerist audiences was the primary goal. Seeing how quickly this idea of Cameron’s upcoming transplant being a potential ‘Jurassic Park’ situation amused me. I’d snorted, and turned to my mother and declared “I wonder what Malorie Blackman would have made of Masie Lockwood!”

The idea of this book offering insight into whether Cameron had the right to live over Trudy or the other pigs, and the ethics of the scientists that helped him reminded me of a comic strip I once saw online, which commented on how people expect divine intervention in a miraculous, not coincidental. A man was drowning, and rejected the assistance of boats that passed him by and offered help, under the guise of waiting for God to save him. When he drowned, God was exasperated, because he’d sent those boats. Not to make the book religious, because it wasn’t, but the argument that the technology had been created and honed to help people, and rejecting it, instead of trying to save your life seemed like a similar potential experience to the man in that comic strip.

I think the scene that rubbed me the wrong way the most was probably when Cameron’s trust was thrown back in his face. The confidential nature of his procedure was breached the second he told his best friend everything, but, in a thirteen-year-old boy telling his mother why he was so worried about his friend going in for life-saving surgery, his parents saw the potential for that secret to solve all their money problems. It was opportunistic and malicious, even if unintentional. It showed the double edged sword of being in the loop about juicy information you could sell to the tabloids. It wasn’t Marlon’s fault. He didn’t know what would come of it when he confided in his mother.

The commentary on life and living your best life was well placed, nuanced and demonstrated a graceful depiction of how Cameron felt, and the support of the people around him. He doesn’t feel touched by death now its no longer looming over him like a stormcloud. I feel like that quick means of bouncing back truly incapsulates the spirit of youthful ignorance. You can know pain. You can know chronic pain, illness, injury, distress etc. but there’s something about the promise of the future that makes it easy to just brush yourself off and keep moving forward. Children are fearless in that respect.

When I was fourteen, me and my cousin tried to go down a 90 degree drop slide at an adventure park, small children launched themselves off without hesitation. But there is a horribly embarrassing video of us backing away from the edge and chickening out. Children were launching themselves off the edge of the slide and going down without issue, but we were afraid. Not of dying, but of the drop, or hurting ourselves. It was the thrill that kept flocks of children going up there while we ran away. Cameron has his own stood at the top of the slide moment toward the end of the book, and seeing him make his decision was hard to read. A boy full of vigour was just so tired. So, so tired.

The story was incredibly poignant, and it hit me particularly hard. I kept thinking back to one of the stories in Sequoia Nagamatsu’s book of short stories, ‘How High We Go In The Dark’, which I reviewed back in September of last year. The story ‘Pig Son’ in her collection, made me even more squeamish about how Cameron insisted on meeting Trudy, the pig who would die for him.

This wasn’t an easy read at all, but it was certainly an interesting one. I think its an important one, too, one that sheds a lot of light onto the pain of being on a wait-list for organ donations, into the parasitic nature of the press, and how hypocritical protests can be.